by Maria da Graça Prado

Long before the first shovel hits the ground, the future of an infrastructure project is already being shaped. Needs are identified, locations are selected, and investments are prioritised. If transparency during project delivery is essential for integrity and accountability, clarity at these earliest stages is just as critical. Without it, priorities can drift away from social needs, project choices can be biased from the outset, and integrity risks can open the door to corruption at later stages of the project cycle.

The use of data standards can help mitigate such early risks. By streamlining complex project information, data standards give stakeholders clearer insights into the factors driving early-stage decision-making.

As part of the Responsible Infrastructure Investment campaign, a broader initiative funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office focused on project appraisal and selection, we conducted pilot studies in Kampala, Uganda and Jalisco, Mexico. The goal was to test a subset of our newly developed data points from sustainability and climate finance modules linked to the early stages of the project cycle. For COP30, we’re highlighting the work of this project in supporting COP30 goals, such as connecting climate change to individuals and the economy, and accelerating implementation.

Approach

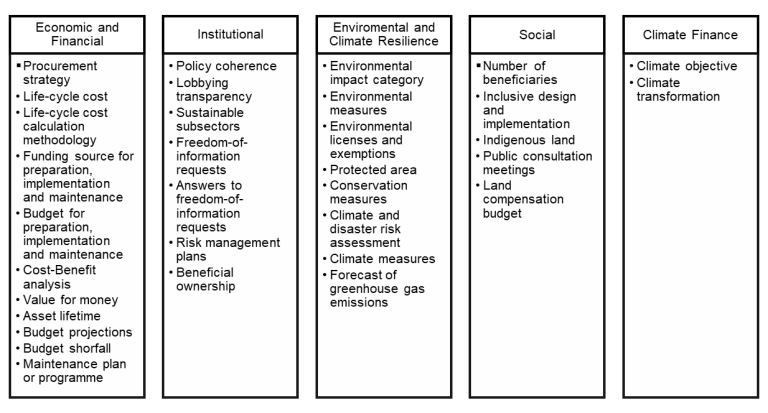

The pilots included a data modelling exercise that used data points to collect information from a sample of infrastructure projects in each country. The data points included metrics such as life-cycle cost, value for money, and budget projections under the economic dimension; policy coherence, lobbying transparency, and beneficial ownership under the institutional dimension; environmental, conservation, and climate measures under the environmental and climate dimension; number of beneficiaries, public consultation meetings, and land compensation budget under the social dimension; and climate objective and climate transformation under the climate finance dimension. The data modelling was followed by an analysis of the insights generated to identify lessons for improving public infrastructure planning.

The sample included 23 projects. In Uganda, the sample focused on road projects, while in Mexico it covered a broader mix, including road, maritime, rail infrastructure as well as urban development projects. While relatively small, the sample represented a significant infrastructure investment of over £1 billion and was complemented by engagement with procuring entities, local political leadership and communities affected by the projects. A total of 565 people participated in the community dialogues.

Key insights

In Kampala, the analysis revealed a clear divide between internationally and domestically funded projects. International projects often conduct detailed technical assessments that look at economic, environmental, climate and social factors. By contrast, domestically funded projects were frequently backed by little or no appraisal documentation, making it hard to understand how project priorities were justified.

In Jalisco, the analysis highlighted a lack of a consistent approach as projects with similar budgets were subjected to different appraisal processes. Even where the same appraisal method was used, the quality and depth of the available information varied, creating ambiguity in appraisal and decision-making processes. Without clear benchmarks or public justification for differing processes, decisions can become more vulnerable to discretionary interpretation. Even when no wrongdoing occurs, ambiguities can give rise to perceptions of favouritism, bias or undue influence in decision-making.

Across both pilots, economic considerations were consistently a primary driver of project selection, while environmental and social factors received comparatively less attention. Limited public dialogue in setting priorities was highlighted during community engagement. Local populations voiced concerns that decisions often felt top-down and disconnected from social or environmental realities, leading to infrastructure projects serving economic needs rather than people and the planet.

The use of CoST targeted data points also helped identify important gaps in decision-making and planning processes. These included areas needing greater transparency – such as lobbying relations, beneficial ownership of contractors, and climate finance tracking – as well as improved documentation, like records of community engagement and clearer links between projects and long-term strategic plans. The findings also pointed to the need for improved procedures, including updating environmental and social assessments in the event of delays and ensuring that maintenance budgets are properly planned and secured from the outset for adequate project sustainability.

Availability of social information in appraisal was also limited, with the number of project beneficiaries emerging as the most consistently published data. Considerations of gender impact focused more on employment equality during the construction phase, with less attention given to women’s participation in planning.

Conclusion

More than merely assessing transparency gaps, the pilots demonstrated the practical value of CoST data points in guiding planning officials on the type of information that should be considered to ensure an objectively grounded selection and decision-making. For donors and investors, the data points offer a standardised set of criteria to assess whether projects align with sustainability goals and present manageable risks. Meanwhile, civil society can use these data points to question when information is missing, incomplete or inconsistent.

Both CoST Uganda and CoST Jalisco acknowledged that the exercise was valuable in highlighting opportunities to improve internal systems. In Uganda, the CoST team is discussing with local authorities how to use greenhouse emission data and the climate finance data points to better reflect the growing relevance of climate-related investments in the local infrastructure portfolio. As Dr. Serunjogi, the Kawempe Division Mayor, remarked: “The climate crisis is here to stay. We must stop reacting and start planning—with our people, not just for them.” In Jalisco, the CoST disclosure portal was already adapted to receive the new data points, with a dedicated area for ‘sustainability’ aspects and eight data points identified as a starting point for implementation.

After the successful pilot in these countries, Malawi is now leading the way by adapting its procurement portal, the Information Platform for Public Infrastructure (IPPI), to incorporate the climate finance module into its regular publication routine, introducing a new level of transparency to climate infrastructure investments.

For COP30 we are highlighting the work of this project to support climate commitments and the importance of aligning infrastructure investment with climate goals, using tangible data points to ensure results.

Maria Prado is our Lead Research and Policy Adviser, supporting CoST through the analysis and evaluation of programme results and providing evidence-based recommendations to enhance governance in the sector. Maria is a legal professional with expertise in construction and infrastructure, with experience in contract management, compliance, and dispute resolution.